According to ancient feline DNA analysis, domestic cats are likely descended from the African wildcat (lat. Felis silvestris lybica) several thousand years ago. However, selective cat breeding only appeared over the last 50 years, which in evolutionary terms is a very short time for robust genetically different sub-populations within an animal species to form.

Selective cat breeding has also historically been focused on aesthetic features (coat color, coat texture, and other traits defined by a single gene variant), rather than genetically complex body structure or functional/behavioral traits (as is the case in dog breeding). This has resulted in some cat breeds being defined by a single gene variant (responsible for a curly coat, for example) while sharing a multitude of other variants associated with common life history and geographic origin with other, visually different cat breeds. It also happens that cats with very different genetic makeup are classified as the same breed simply due to visual similarity.

To complicate matters further, cats are significantly under-represented in genomics research, especially compared to dogs. To put things in context, researchers from the 99 Lives cat genome project rejoiced when they sequenced the genomes of 200 domestic cats (double their initial goal), while the Dog10K Consortium is aiming to sequence the genomes of 10,000 dogs and wild canids.

Feline genetics is an understudied area of pet health

The vast differences between cats’ and dogs’ evolutionary histories and the disparity in genomics research available mean that DNA-based breed analysis is significantly more challenging in cats than it is in dogs. To equalize the playing field, we need a lot more cat genomes sequenced than what is currently publicly available. Basepaws’ mission is to close the gap between the feline and canine genetics scientific fields.

Basepaws’ science confirms known events in cat breeding history and furthers our understanding of the genetic relationship between different breeds.

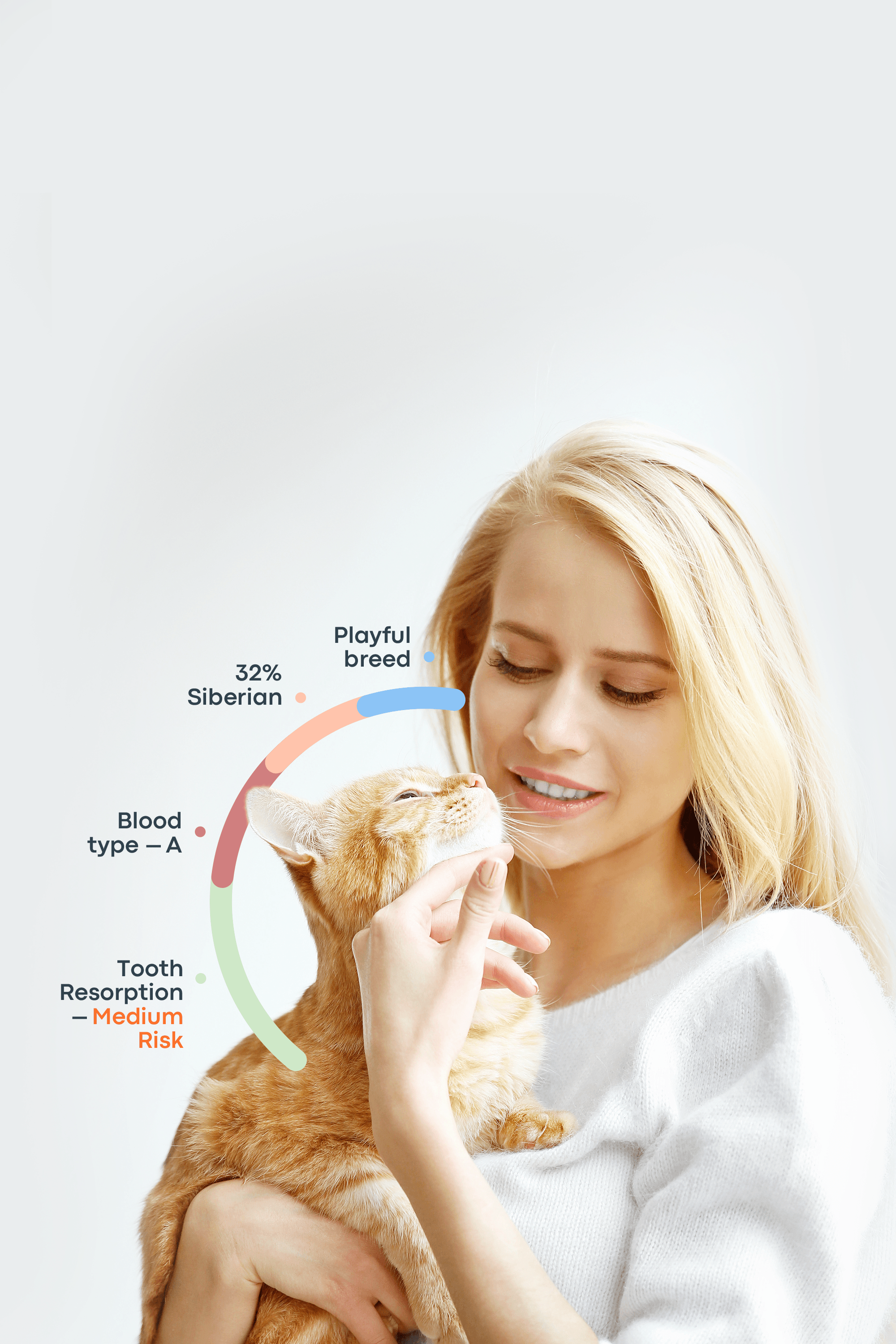

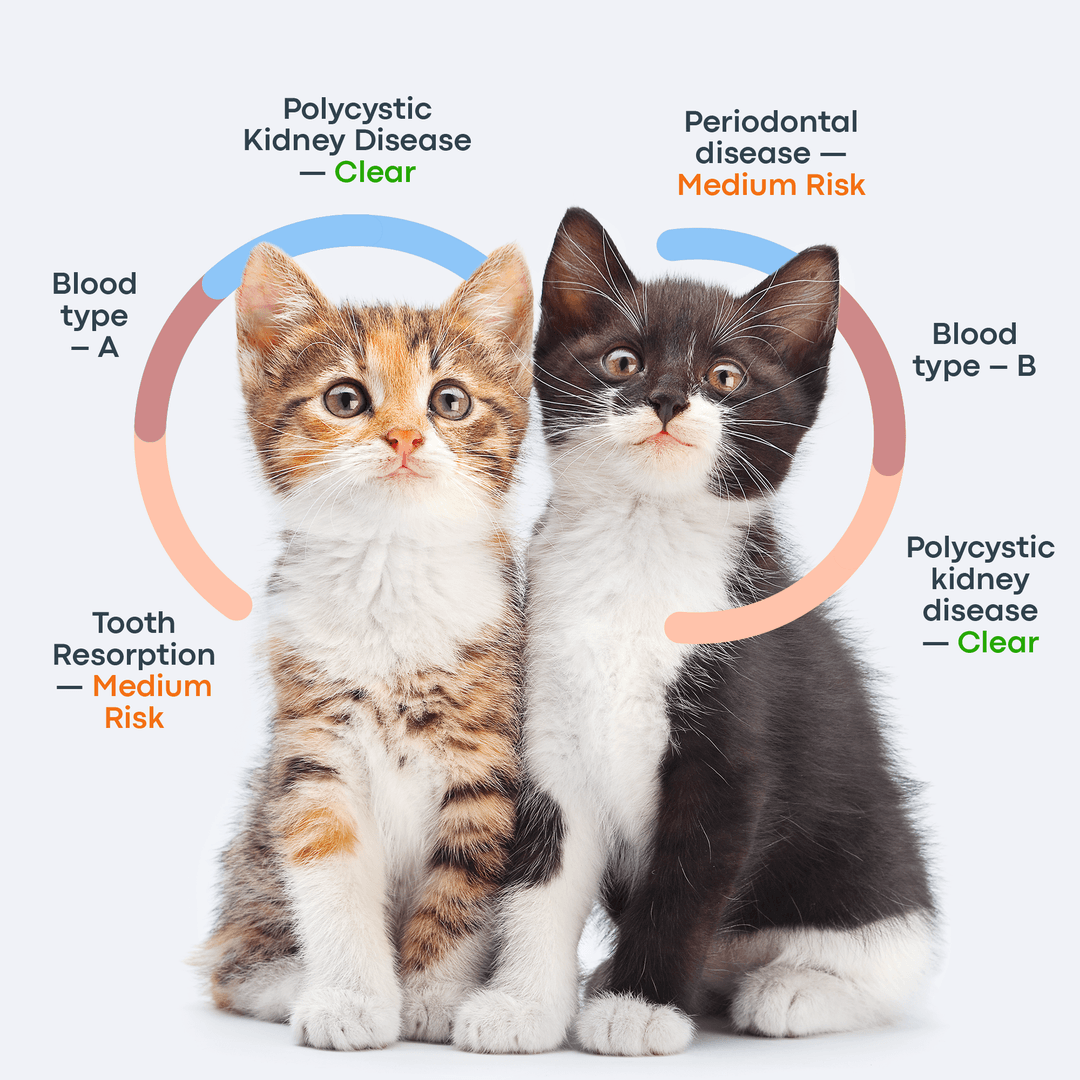

Basepaws is constantly sequencing purebred and mixed-breed cats’ genomes at high depth to compile the world’s largest feline genomic reference database. This resource allows us to identify small genetic differences between breeds and perform accurate feline breed analysis. We currently have 18 feline breeds represented in our database and are continuously adding more. We performed a principal component analysis (PCA) on our high genome coverage purebred samples to visualize the underlying genomic difference between cat DNA samples and observe population segments. We called this analysis the breed genetic proximity map.

Basepaws’ Breed Genetic Proximity Map

a diagram of the different types of cats

Our genetic proximity map depicts the genetic relationships between cat breeds currently included in the Basepaws breed report. The breeds are grouped into four clusters according to their genetic similarities. Eastern breeds are genetically most distinct from the other breeds in our analysis. Eastern breeds include Birmans, Burmese, Oriental Shorthairs, and Peterbalds. Western cats are the largest group in our database. Abyssinian, American Shorthair, Maine Coon, Norwegian Forest, Siberian Forest, Ragdoll, and Russian Blue have all been grouped within this cluster. However, British Shorthairs and Egyptian Maus are genetically related to both Western cats and the neighboring groups of Persian and Exotic cats, respectively. Persian breeds include Exotic Shorthairs, Himalayans, and Persians. Exotic cats include the hybrid bred Bengals and Savannahs.

The isolation of the Eastern breeds cluster

The most prominent observation in our genetic proximity map is the isolated clustering of the Eastern breeds. The Eastern breeds group is clearly genetically separated from other breed groups, which is in agreement with previous findings from Prof. Leslie Lyons’ group at the University of Missouri. Prof. Lyons’ study included Birman, Burmese, Havana Brown, Korat, Siamese, and Singapura cats of Southeast Asian origin, and found that they formed a distinct phylogenetic group from the Western breeds.

Our findings indicate that Eastern cat breeds were all created from a small number of related parent breeds.

Although there aren’t many records available about the evolution of most Eastern breeds, it is thought that the Siamese breed has been outcrossed to (or used for the creation of) a number of other Eastern breeds, including Burmese, Birman, and Oriental Shorthairs. One fact we know is that the Oriental Shorthair has genetic roots within the Siamese group and was used for the creation of Peterbalds. This would explain the clustering of these breeds so close together on our genetic proximity map. There are no available records about the creation and early breeding programs for the Birman and Burmese. There are suggestions, however, that the Siamese was used to “fix” certain “desirable” traits in the Burmese cat, as well as maintain a small population of the breed.

Clustering of the Western, Exotic, and Persian breed groups

The Western, Exotic, and Persian breeds clustered closer together than the Eastern breeds. This indicates the occurrence of cross-breeding between some of the breeds within each of the three groups.

The Persian breed is one of the oldest known cat breeds in the world. It is in close proximity to the Western breed cluster, which is consistent with previous findings. The Persian breed is commonly used for the creation (or “conformation”) of many other cat breeds, such as the Exotic Shorthair, which explains the clustering of these two breeds together on our map. Himalayans were also created from the Persian breed (outcrossed to the Siamese), as confirmed by the genetic proximity of the Himalayan breed to the Persian breed on our map.

The Western breed cluster shows genetic proximity to both the Exotic and the Persian breed groups. The British Shorthair breed lies at the intersection of the Western and Persian clusters. British Shorthairs were nearly extinct after World War II and, as a consequence, were outcrossed to Persians (among other purebred and mixed cats), in order to maintain and re-establish the breed.

The Egyptian Mau, although previously placed within the group of Western breeds, shares common markers with both Western and Exotic cats, and lies at the intersection of the two groups on our genetic proximity map. Egyptian Maus were crossed with servals (lat. Leptailurus serval) in Savannah breeding programs. The breed was also outcrossed to the Asian leopard cat (lat. Prionaliurus bengalensis) for the creation of Bengals. Another breed that was commonly used in the breeding program of the Bengals is Abyssinians, which agrees with their relative genetic proximity to the Exotic cat’s group.

With the exception of the Egyptian Mau, the Exotic cluster forms a distinct cluster from related Western breeds due to hybrid cats’ high genetic diversity inherited from wild ancestors.

The placement of the remaining Western breeds in our genetic proximity map is mainly consistent with the findings from Prof. Lyons’ lab. Norwegian Forest, Siberian Forest, Ragdoll and Russian Blue cats all clustered in a relatively close genetic proximity. This was expected as all these breeds originated in Europe from mixed European domestic cats. However, interestingly enough, breeds of American origin (Maine Coon and American Shorthair) also clustered within this group. It is consistent with the results obtained in a study by the University of California – Davis where it was discovered that Maine Coon and American Shorthair are genetically close to each other, as well as Western European cats. It can be speculated that this is due to the fact that these cats were developed from mixed-breed cats brought over from Europe to the US, and there wasn’t enough time for them to become genetically isolated from their ancestors. The Abyssinian cat breed is an interesting member of the Western breed cluster.

Although originally of Egyptian or Southeast Asian origin, it is a breed that was developed and largely bred in the UK for many years. Therefore, it was likely genetically mixed with European cats over time, which would explain its position in our genetic proximity map.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of our customers for joining our mission and helping us discover more about cat genetics and the history of cat breeds. Thank you for all the support, trust, and patience. We would also like to give special thanks to the pet parents of Tigra, Rudzik, Bastu, Cledus, Snowman, Samson, Theia, Ms. Kitty, Toki, Wolfie, Luna, and Ruby who purchased our high-depth WGS service. Without you, none of this would be possible.

We are only just getting started and will continue to drive advances in feline science and genetics. We are excited to share all our future discoveries with you! If you would like to join our journey and discover more about your cat’s breed ancestry and health, find out more about our product here.