Featured Post

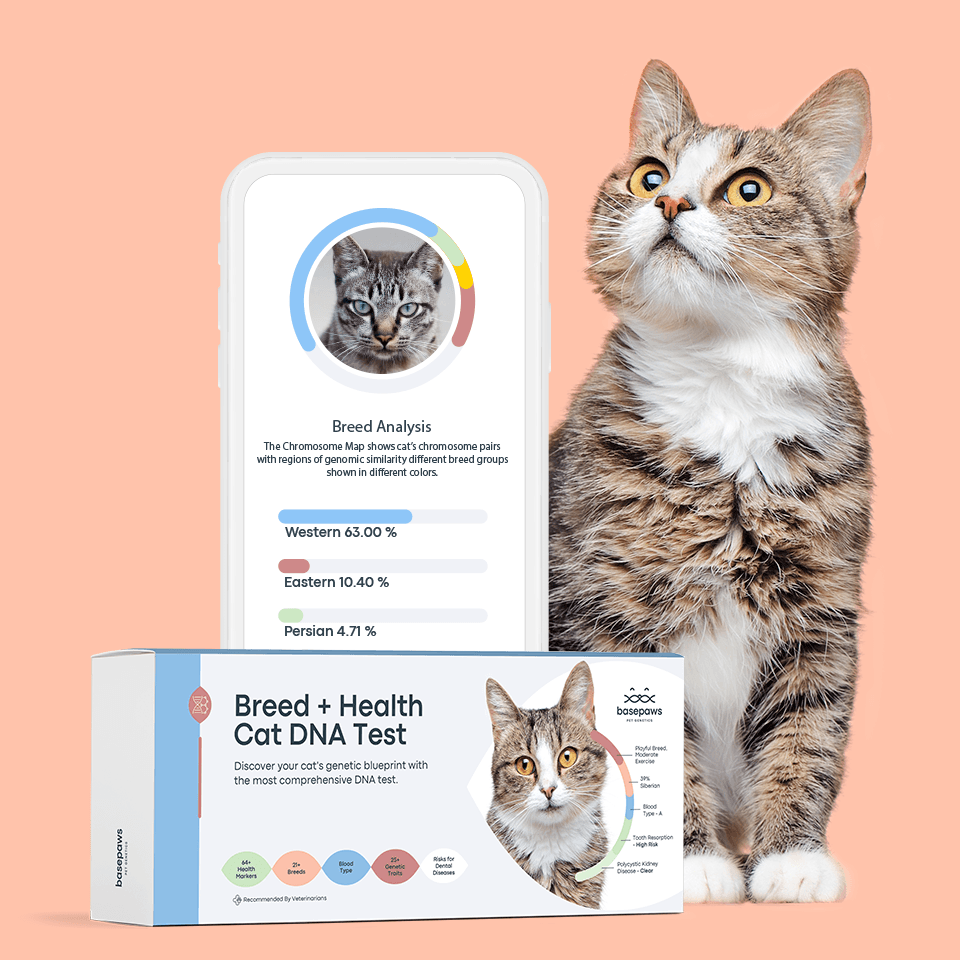

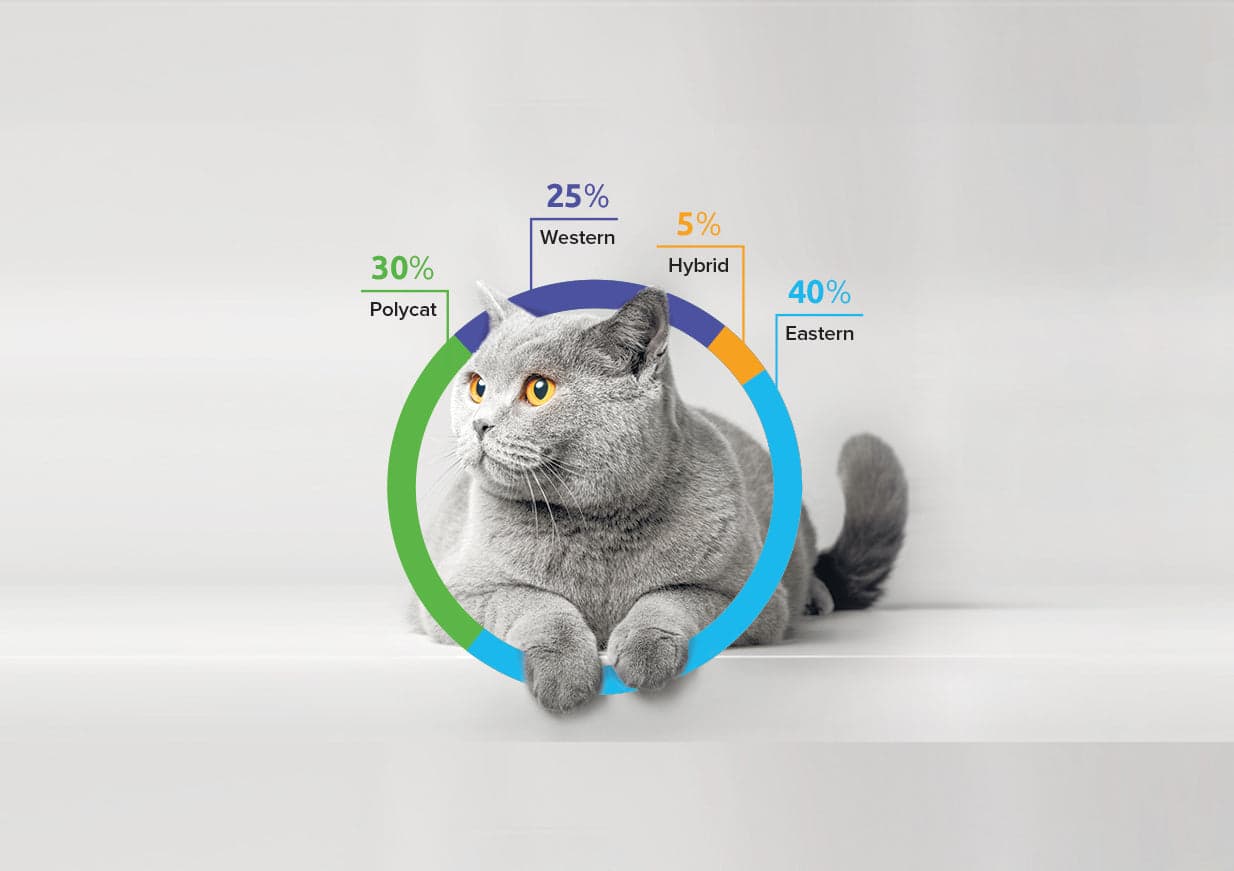

Basepaws provides pet parents like you with comprehensive DNA tests and informative resources to help your cat to live their best life. A quick and easy at-home swab of your kitty's mouth offers a world of valuable information about their unique breed mix, genetic predisposition to 43 health conditions, and genetic traits responsible for their fabulous appearance.

Screen for health risks and diseases

Recommended by top vets with decades of experience

21 breeds

64 genetic health markers

50 genetic trait markers